|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

ARTEXT : La Biennale di Venezia

TELECO SOUP

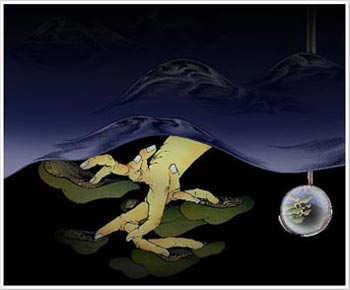

For this installation, Yanagi will take the Takamasa Yoshizaka-designed Japan Pavilion built in 1956 and In Venice, "TABAIMO: teleco-soup" will continue that trajectory through an immersive multimedia environment that incorporates the unique characteristics of the Japan Pavilion in the Giardini, completed in 1956 and designed by the architect Takamasa Yoshizaka. In Japanese the exhibition title, "teleco-soup," connotes the idea of an "inverted" soup, or the inversion of relations between water and sky, fluid and container, self and world. Coined by the artist, this phrase builds upon an intellectual tradition in Japan that grapples with the country's identity as an island state, or what in recent years has come to be known as the "Galapagos Syndrome," originally used to describe the incompatibility between Japanese technology and international markets but now applicable to multiple facets of Japanese society in the age of globalization. The structure of the exhibition further references a proverb attributed to the Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi, "A frog in a well cannot conceive of the ocean," and an addendum to the Japanese version of the same, "But it knows the height of the sky." Through the use of a multi-channel animation projection and mirror panels, Tabaimo will transform the interior of the Japan Pavilion into a well and the open space beneath the Pavilion, which is raised on pilotis, into the sky. The animation begins with images of a minute cell that evolves into a body, and continues with depictions of Tabaimo herself as well as of all the people currently living in Japan and Japanese society as a whole, evoking a continually expanding space. The succession of images will lead to a recognition of the unimaginable breadth of the well – or contemporary Japan – and through the installation's anti-gravitational orientation will connect to an infinite depth/height in the eternal world of the sky below, visible through an aperture in the floor at the Pavilion center. In this way extending beyond the confines of the Pavilion, the installation will destabilize relations between up and down, interior and exterior, broad and narrow perspectives, and immerse visitors into a bodily experience that asks them to question, Is the world of a frog living in a well really so small? And, How can we negotiate the points of contact between the individual and the communal – how do we negotiate our own Galapagos Syndromes? D. : Tabaimo, the set up of your installations often makes viewers watch your videos in specific ways. Is it important to you to control the viewer’s experience of the work? Tabaimo : It’s the same for all my works: it’s not so much about controlling the viewer’s point of view as it is about setting up a space which will encourage viewers to be proactive in how they look at the work. What interests me is the idea of setting up a space — be it narrow, dark, or on a slope — somewhere which is not easy to stand, somewhere which makes a variety of demands on how you approach it: basically an environment which denies you a comfortable viewing experience. I deliberately create those kinds of environments for the viewer to view the work in. That being the case, for some people, just the experience of being in this uncomfortable space is enough to make them give up on viewing the work, but there are other people who continue to look at the work in spite of the adverse conditions. It all depends on the viewers’ choice: I don’t just put the work in front of them and make it a comfortable experience for them – they need to be proactive in their viewing if they are to understand what I’m saying. I think the viewers’ stories themselves are the work, so by making the work together in a sense, by setting up spaces which cause the viewer discomfort — spaces which have elements in them that need to be overcome — the works become a participatory experience. D. : The alteration or obliteration of the human body is a theme that recurs throughout your work: for example, your drawings of distorted hands intertwined with the bodies of insects or the image of a baby being born out of a woman’s nose. Do you have any particular thoughts about the human body? Tabaimo : I think that animation is a very important form of expression, but in order to show something in animated form, you have to get rid of all excess features or else you will often find yourself unable to express what you’re aiming for. So I get rid of all the things I think are unnecessary in the images and… for example, babies are normally born from between a woman’s legs, but I didn’t feel it necessary to express that in the animation. Everybody already knows how babies are born, so I thought that if I portrayed it in a different way, perhaps I could imbue it with a different meaning, that perhaps it’s possible to express a deeper insight into something in only an instant. I think the human body is particularly open to those possibilities. We are used to seeing our hands attached here on the ends of our arms, and at this age we all know that babies grow in the womb and are either born by Caesarian section or from between the legs, so I think by subverting those preconceptions, it makes it possible for viewers to ask why things are the way they are, and search for the answer to that question. So I don’t feel it necessary to portray the world as it really is.

Curatori : Yuka Uematsu Artisti : Tabaimo

Web site : http://www.jpf.go.jp/venezia-biennale/ |

||||

Artext © 2011 |